Obturator to Femoral Nerve Transfer for Femoral Nerve Palsy Using a Modified Technique-Juniper-Publisher

Juniper Online Journal of Orthopedic & Orthoplastic Surgery

Introduction

Though uncommon, femoral nerve palsies are

potentially devastating injuries which can occur as a result of

penetrating trauma or malignancies, however the most common cause is

inadvertent iatrogenic injury following intra abdominal surgery such as

gynaecological/vascular surgery or total hip replacement [1].

We present a case of iatrogenic femoral nerve injury with a delayed

presentation resulting in an 8.5cm nerve defect, which was managed with

both traditional cable grafting and a contemporary nerve transfer

utilising a modification of an existing technique.

Case Report

In September 2015 a 49 year old female presented to

our institution 6 months following a laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair

which had resulted in a complete transection of the right femoral

nerve. There was a 6 month delay in diagnosis of the iatrogenic injury.

The patient had an extraperitoneal exploration of the right groin which

confirmed the diagnosis, and an 8.5cm nerve defect at the level of the

inguinal ligament was cable grafted with 4 cables sural nerve grafts.

After discussion with the patient and appropriate review of the

literature and cadaver dissection, the patient had a nerve transfer

procedure 3 weeks following the cable grafting.

Procedure 1

In conjunction with General Surgical colleagues a

supra- inguinal extraperitoneal approach was performed exposing the

femoral neurovascular bundle in the right iliac fossa. This incision was

then extended distally and the inguinal ligament was divided and later

repaired for exposure of the nerve. A prominent neuroma was identified

where the nerve was divided, associated with mesh and metallic tacs from

the hernia. Ipsilateral sural nerve was harvested and a reversed cable

graft using four 8.5cm cables was used to close the defect.

Procedure 2

Nineteen days after the first operation an obturator

to femoral nerve transfer was performed. An anterior longitudinal

incision incorporating the existing scar was used to expose the distal

end of the cable graft, the distal femoral nerve and its terminal

branches. The medial sensory branch and the branches to the rectus

femoris and vastus lateralis were identified and the latter two

confirmed to be non functional with electrical stimulation. The anterior

branch of the obturator nerve was identified and traced distally to

identify the branch entering gracilis. The nerve to gracilis was

transected distally and passed over the adductor longus muscle to reach

the femoral nerve. It was then redirected sub muscularly under the

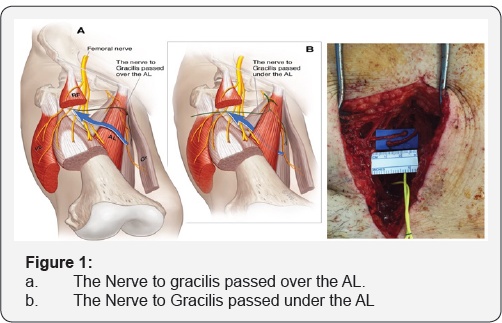

adductor longus muscle (Figure 1).

With this more direct route, the end of the gracilis branch was able to

reach four centimetres more distally. The nerve to gracilis was then

neurotised to the femoral nerve branch to rectus femoris. The

neurotisation was undertaken under microscope magnification with 9-0

S&T sutures (Insert Trade Details) and reinforced with Tiseel™

fibrin glue (Baxter pharmaceuticals).

Discussion

Complete femoral nerve injuries are uncommon and

usually leave the patient with significant morbidity, requiring orthoses

for simple mobility. Traditionally a nerve defect of this size would be

managed with autologous cable grafting as initially performed. The

large size of the nerve defect and also the significant distance from

the distal end of the graft to the neuromuscular junction result in a

poor prognosis for functional recovery. Whilst tendon transfers provide a

good reconstructive option for some neurological injuries, (example

radial nerve palsy), there are few satisfactory options available for

femoral nerve palsy. Fischer et al. [2]

reported on a hamstring transfer after soft tissue sarcoma resection

with significant complications and modest results of extension force.

Nerve transfers have been well described in the literature for upper limb reconstruction [3].

There is in contrast a paucity of reconstruction options in lower limb

nerve injury. Nerve transfers provide an attractive option, as

performing the neurotisation distally minimises the distance and hence

time required for neural regeneration and ultimately functional

recovery. Motor end plates are known to undergo extensive change post

denervation and functional reinnervation is unlikely beyond 18 months

due to progressive fibrosis [4].

This case also posed further time pressure as referral to our

institution was delayed by 6 months since the nerve injury. By

performing the second procedure of the obturator to femoral transfer,

viable axons were delivered approximately 13cm closer to the

neuromuscular junctions providing greater potential for reinnervation

prior to loss of the motor end plates.

The pattern of the femoral nerve branching pattern has been previously described in a cadaver dissection by Tung et al. [3]. There have only been two previous papers in the literature discussing case reports of 3 similar procedures. Campbell et al. [5]

reported a single case of total obturator to femoral nerve transfer 3

months post schwannoma resection with good functional result. This was

performed above the inguinal ligament. Goubier et al. [6]

conducted a cadaveric feasibility study in 2012 confirming the

possibility of performing a subcutaneous transfer of two obturator motor

branches to the femoral nerve in the thigh.

Tung et al. [3]

reported on 2 cases of a subcutaneous obturator to femoral nerve

transfer for complete femoral nerve injury- 1 performed acutely and the

other 5 months post injury. The second patient was also supplemented

with a superior gluteal nerve transfer after the first patient had

incomplete recovery and an inability to climb stairs. This showed

encouraging results. In our patient we have combined the existing

obturator to femoral nerve transfer and added a cable graft in an

attempt to provide a belt and braces reconstruction. We also determined

that directing the gracilis branch deep to adductor longus rather than

superficial to this muscle provides an increase in effective length of

the nerve, allowing a more distal nerve repair, which is theoretically

beneficial.

Iorio et al. [7]

noted the proximity and potential of the anterior branch of the

obturator nerve to gracilis in femoral nerve injuries. In their

cadaveric study they proposed using this nerve for a donor for cable

grafting, hypothesising that a motor nerve may maximise functional

outcomes. They also noted that the average donor length was 11.4cm. The

anterior branch of the obturator nerve has also been considered for

restoring other neurological losses. In a cadaveric study in 2014,

Houdek et al. [8]

deemed it feasible to transfer the anterior branch of the obturator

nerve to pelvic nerves in order to restore bowel and bladder function.

Interestingly Spiliopoulos et al. [9]

published a case report of the reverse nerve transfer - femoral branch

to obturator to restore adduction following another iatrogenic injury.

They reported a good outcome with full power and normal gait.

Conclusion

We present a novel 'belt and braces' approach for

managing this unusual injury, using a modification of a nerve transfer

which has only been reported in the literature three times previously to

our knowledge.

To read more articles in Journal of

Orthopedic & Orthoplastic Surgery

To

Know More about Juniper Publishers click

on: https://juniperpublishers.com/

Comments

Post a Comment